Bible Translation Comparison

The King James Version has been the standard for English translations of the Bible for over 400 years. The original edition, published in 1611, is hardly decipherable by English speakers today. The spelling and type face were updated in 1769, and it is this edition that has held is place as the most popular English translation of the Bible from that time until today.

The King James Version was by no means the first English translation—it was built upon the work of William Tyndale, Coverdale, Rogers, and other reformers—but it was the first to be “authorized” by the king of England, and the dedication and thoroughness of the translators of that time has been without parallel.

Amazingly, the Bible translation authorized by king James did more than any other work to form and shape the English language, which at the time was fragmented in numerous local dialects. In fact, many idioms in common usage today have their origin in the King James Bible.

Going Back to the Source

The translators used, as their source, the best original language manuscripts available to them in their day. The only Bible “authorized” by the Catholic Church at the time was the Latin Vulgate. The reformers of the 16th century, however, realized that numerous errors had crept into the Latin Bible, and this drove them to go back to manuscripts in the original languages of the Bible—Hebrew and Greek. While the Jewish scholars (Masorites) had done an excellent job of preserving copies of the Old Testament scriptures, the Greek manuscripts were a little harder to come by. Since they were not preserved by the western (Catholic) church, the reformers found several copies of the Greek manuscript that had been preserved generally by the eastern (Orthodox) church, and also by the Waldensees. In 1536, a man by the name of Udo Erasmus compiled and published a Greek edition of the New Testament along with a new Latin translation which he had made. Erasmus had compiled his Greek text from a handful of Greek manuscripts following the eastern (or Byzantine) text type. A few verses Erasmus had to back-translate from the Latin Vulgate, because they weren’t in any of the manuscripts that he had. (One example of this is Revelation 22:19.)

Over the succeeding years, Erasmus’ Greek New Testament was published and re-published, and came to be known as the “Textus Receptus” or “Received Text.” It was the “Textus Receptus” that formed the basis of the New Testament in King James Version, as well as Martin Luther’s German translation and other translations from that era of the Protestant Reformation.

In the mid-1800’s, two scholars B. F. Wescott and F. J. A. Hort did extensive research into the ancient greek manuscripts of the New Testament. Their goal was to decipher, from the extant manuscripts, the reading that was most likely to be the original. In this process, they developed the principles that form the basis of modern textual criticism. In their research, they preferred, in particular, two manuscripts known as the Codex Vaticanus and the Codex Sinaiticus, both ancient manuscripts of an Alexandrian text type.

Wescott and Hort published their Greek New Testament in 1881, and in 1885 the English Revised Version was published, based on the new critical text. In 1901, the American Standard Version was published, as an update to the Revised Version. Today, there are literally hundreds of English translations of the Bible.

Why So Many Translations?

Despite the large and growing number of new English translations, many people still prefer the original King James Version, for various reasons. Many people prefer to use the Bible that they grew up with. Many enjoy the poetic flow of the language. But as time progresses, many young people are having more and more difficulty understanding even the basic language of the King James Bible. For those who are not accustomed to church, the words are like foreign language. For those who are, the words often become cliché, or phrases with lofty and hidden spiritual meanings.

Many people hold to the teaching of the verbal inspiration of Scripture. For these, every word of the Bible is a word spoken by God himself—unerring and unchangeable. Moses, David, Mathew, Mark, and Paul—these men were merely God’s pen, transcribing the words of God Himself. And, in some way, the King James version has come to represent these very words of God—as though the translators themselves, commissioned by King James of England, were inspired by God Himself to write in English the very words that God had written in Hebrew and Greek long ago. Thus, for these people, the King James Version is the only true English Bible there ever was, or ever will be. All others are fake—imposters, corrupted by men who were bent on implanting false teaching into the very Word of God.

Other people take a more moderated approach. They realize the Bible was translated from the original languages by human beings, but argue for the superiority of the Byzantine or Majority text type, or for the Textus Receptus in particular, on the basis of the fact that this was the Bible of the Protestant Reformation. Some view the critical text of Wescott and Hort as being “tainted” or “corrupted” by its association with the Catholic church and the Latin Vulgate. Some argue that Byzantine text type (or Majority Text) is a more accurate representation of the Bible that was used by true Christians over the centuries, while the Alexandrian text may have been corrupted at an early date. There is certainly merit to these arguments.

If a person studies the Bible with a view of verbal inspiration, it would be easy to lose faith in the Bible as a whole. Why? Because no matter how you look at it, there are contradictions, errors, and inconsistencies within the Bible. No matter whether you use the King James Bible, or any other Bible, you will find contradictions. Of course, the contradictions are immaterial—they won’t lead us to believe some false doctrine—but if you take the Bible as the verbally inspired Word of God, you would have to wonder why God appeared to make mistakes!

The Bible itself testifies that it was written by men (see 2 Peter 1:21). God inspired men with the thoughts, but men put these thoughts into words. Really, this is the only reason we can translate the Bible in the first place. Otherwise, we would all need to learn Hebrew and Greek! Even the apostles used a Bible that had been translated from Hebrew into Greek—the Septuagint (which we know today to be a somewhat faulty translation).

When we understand the nature of Inspiration—that men wrote down in human language the thoughts, ideas, and concepts that had been inspired by God—it opens up the possibility and necessity of using a good quality, modern translation of the Bible that expresses those same thoughts, as accurately as possible, in today’s language.

Which Translation?

The variety of modern English translations of the Bible is as varied as the Christian Church itself. There is a huge variety of philosophies among translators, resulting in a whole spectrum of different translations, ranging from Young’s Literal Translation to The Message, from the English Standard Version to the Contemporary English Version.

There are many ways of comparing the translations. Some, like the New Living Translation, are made to be easy to read. Some, like the English Standard Version, try to preserve the poetic flow of language found in the KJV.

Two competing philosophies of translation define a spectrum that can help to describe the various translations: Formal Equivalence (or Word-for-word translation) versus Dynamic Equivalence (or thought-for-though translation). Formal Equivalence takes the literal words of the original language, and translates them into the closest equivalent words in the target language. This insures that nothing is lost in the translation. Of course, this assumes that it’s possible to translate every word or phrase into an exact equivalent—in practice there are many times when there isn’t a direct equivalent, and often “Formal Equivalence” sacrifices readability for the sake of exact accuracy in translation.

On the other end of the spectrum, Dynamic Equivalence attempts to express each thought in the original text by using the most natural expressions and idioms in the target language. This makes for better readability, and can really make the Bible come alive. Often, the meaning of the arguments and narrative of scripture can be obscured in difficult language, and a dynamic equivalence translation can bring out that meaning in a clear and powerful way. On the other hand, the reader must rely more closely on the translator’s judgment in understanding and “interpreting” what the original author intended to say. Often, idioms and expressions in the original language are lost altogether, and there is more opportunity for a translator’s bias or doctrinal understanding to find its way into the resulting text.

Besides the formal vs dynamic equivalence debate, there are many other points of difference. Which source manuscripts to use, and how much weight to give to variant readings from different sources, give rise to more discrepancies. Also, how does one deal with changes in the English language, such as the use of gender-specific pronouns to translate Biblical thoughts that may be gender-inclusive? Translators must choose how to translate terms with certain theological connotations, such as “God,” “Lord,” “Gospel,” or “Hell.”

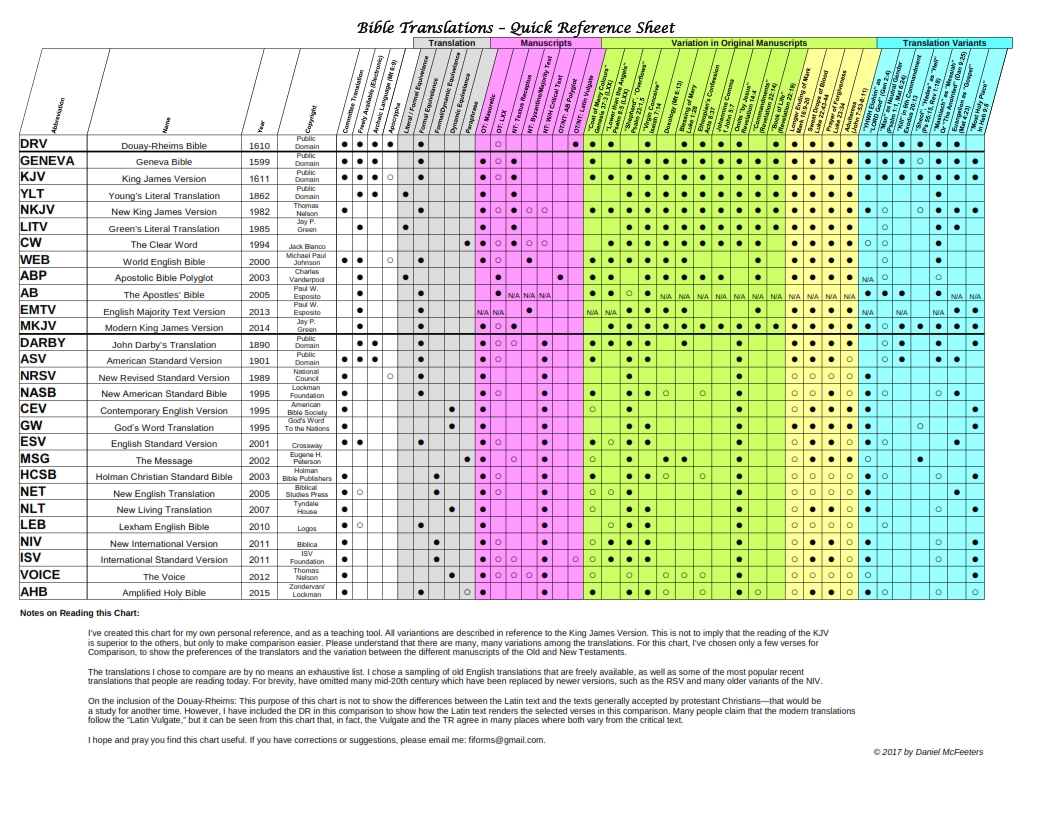

In my study last year for the sermon series, “The Story of the Word,” I did some research into various Bible translations. As many others have found as well, I found a great deal of similarities and differences between the various translations. In order to better understand the philosophy of the translators, I created a chart that compares the various translations, including information from the preface of each translations, and select verses that highlight the differences between manuscripts or choice of words in translation.

The results were quite interesting, and I was honestly surprised on a few counts. I have decided to upload my chart here on my blog, for your enjoyment and study. I make no claims as to its accuracy, other than that I’ve tried my best to be fair and impartial. As noted on the chart, the comparisons are worded so that the KJV has a “dot” in every column. This isn’t to imply that the KJV is the “best”, but to give a frame of reference to compare the other translations to.

Download Bible Translation Matrix as PDF

Download Bible Translation Matrix as Excel Spreadsheet

Some Notes on Methods of Comparison

Year

The era when a translation was made affects how easy it is to read to a 21st century reader. Language is constantly changing, and words have different meanings depending on when they are written.

Copyright

This may seem trivial, but in the 21st century, whether a Bible can be distributed electronically or not can determine how widely it is used on electronic devices, and so how widely it is read.

Committee Translation

Good translations for study are ones that have had many scholars working together to create. If a translation is made by only one individual, it may be more likely to reflect the theological views of that individual.

Translation Philosophy

I used 5 categories to represent the spectrum from literal/formal equivalence, to dynamic equivalence/paraphrase. Many times this was easy to determine from the preface of the Bible. Other times, I used my best judgment to place it in comparison to other translations. This also depends on specific passages, which may be more or less paraphrased in different translations, so this is a broad generalization at best.

Manuscripts

Which source manuscripts were used in translation. For the Old Testament, there are the Masoretic text (Hebrew), the LXX (ancient Greek Translation), and the Vulgate (Latin translation of the LXX). The apostolic Bible Polyglot is a separate variant of the LXX. For the New Testament, there are the Textus Receptus (Reformation Greek New Testament), the so-called “Majority Text” (a family of critical texts which favor the Byzantine text type) and the “W/H Critical Text,” following in the tradition of the Westcott-Hort critical text and the Nestle-Aland/United Bible Society Greek text.

What becomes apparent in this comparison is that most Bible translations don’t follow strictly to only one of the manuscripts / families, but tend to pick and choose from more popular readings in each.

Textual Variants Showing Differences in Original Manuscripts

Genesis 37:3 “Coat of Many Colors

The idea of “many colors” in this verse comes from a Septuagint reading. The Hebrew uses a rare term that most-likely means a coat of “long sleeves” or “finely woven.” In any case, it was a coat of royalty. However, this verse tends to show the influence of the LXX and historical translations on many of the modern “critical” translations.

Psalm 8:5 “Lower than the Angels”

The reading of “Angels” in this verse comes from the LXX. Hebrew uses “Elohim” (God or heavenly beings).

Psalm 23

The Vulgate (from LXX) does not contain the word “shepherd” in the 23rd Psalm, but just the idea that “God leads me.” Verse 5 in KJV says “my cup runneth over.” In the Vulgate/LXX, the same verse gives the meaning of being drunk with intoxicating wine.

Isaiah 7:14 “Virgin”

The Hebrew term for “Virgin” does not necessarily imply virginity, and could simply mean a “young woman.” The specific term for “virgin” is found in the LXX, and because of its application to the birth of Christ it is almost always translated as “virgin.”

Matthew 6:13 Doxology

“For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory forever. Amen.” These words are found in the TR and Majority Greek texts, but not in the Critical text or the Vulgate.

Luke 1:28 Blessing of Mary

The last words “Blessed art thou among women” are omitted in the critical text, although they are present in the TR, Majority Greek, and Vulgate.

Acts 8:37 Ethiopian’s Confession

This verse is found in the TR and Vulgate, but omitted in Majority Greek and Critical texts.

1 John 5:7

The famous “Johannine Comma” has very little textual evidence as being original. It was found only in the Vulgate, and was a late addition to the TR (likely from pressure on the part of the state-church at the time). It is not found in Majority Greek or Critical texts. The inclusion of this verse is a strong “proof-text” for the doctrine of the Trinity, but its exclusion does not necessarily destroy the teaching.

Revelation 14:4

The words “by Jesus” are found in the Majority Greek text, but not in other manuscripts. Not a major difference but I have included it on the chart to show the variation between TR and Majority Text translations.

Revelation 22:14

“Blessed are they that do His commandments” is the reading in TR / Majority Text. “Blessed are they that wash their robes” is found in Vulgate and Critical Texts. A well-known difference with deep theological implications.

Revelation 22:19 “Book of Life

The term “Book of Life” was introduced into the TR from the Vulgate, because Erasmus did not have any Greek manuscripts that contained this verse. All Greek manuscripts read “Tree of Life.”

Omitted Passages

Mark 16:9-20, Luke 22:43-44, Luke 23:34, John 7:53-8:11

These passages are not considered as original by the compilers of the Critical Text, although they are present in the Vulgate, TR, and Majority text. Nevertheless, they are included in all major translations, even though they are bracketed in some translations (indicated by a hollow circle on the chart).

Textual Variants Showing Differences in Translation Philosophy

Translation of God’s Name

Starting with the ASV, some translations break with the tradition of using the terms “Lord” and “God” and instead transliterate God’s name as “Yaweh” or “Jehovah.” I just referenced one verse (Genesis 2:4) on the chart, but it’s included to show the trend of translating God’s name.

Gender-Neutral Terms

Again, this has become a big debate, about whether to use gender-neutral English terms to translate terms in the Bible that are likely to be gender-inclusive.

“Kill” in the 6th commandment

Another comparison that indicates how precisely the translators chose English terms to match the Hebrew/Greek words. The 6th commandment prohibits “Murder,” and the Hebrew has different terms to indicate different types of “killing” just as we do in English. The KJV incorrectly uses the generic term “Kill,” and this tradition is followed in a few other translations, although most new translations use a more specific term.

Translating terms for “Hell”

Several Hebrew and Greek terms are translated into the English word “Hell” in the KJV. Newer translations tend to transliterate these, or use more specific terms, to avoid confusing “hell” (torment) with “grave.”

Application of Daniel 9 to Jesus

This is in reference to the Seventh-day Adventist teaching of the 70 weeks’ prophecy of Daniel 9. Many modern translations, likely due to evangelical influence, have re-worded the prophecy so that it can be easily understood to apply to someone other than Christ, despite the use of the Hebrew term “Mashiach” or “Messiah.”

Translating the term “Gospel”

The term “Gospel” has come to be a purely theological term, and many translations more accurately translate the meaning of the word as “Good News.” This correlates with a tendency to do the same for other theological terms, making the translation more understandable for the common person.

Hebrews 9:8 “Holiest of all”

Another verse with possible implications for the Seventh-day Adventist understanding of the heavenly sanctuary and Christ’s ministration. Some translations translate as “Holy Place” or “Holy Places,” others as “Most Holy Place” or similar.

—

If you have enjoyed this article, please also see my recent message, “Which Bible Translation?”

Hello Daniel, How about the Modern English Version?

Hi Steve, regarding the Modern English Version, it is actually very similar to the NKJV. It’s a fairly new translation (2014), and I guess I just overlooked it when I put the chart together.

I’ve updated the PDF version of the chart here to include the MEV.

Unlike most modern translations, the MEV is a direct translation of the TR and the Masoretic text of the reformation era, just like the KJV. From what I can tell, no attempt is made to do any textual criticism of the source text. Even the NKJV (although also from the TR New Testament) includes very helpful footnotes comparing differences in the source text. For example, there are a few passages in the TR that virtually all scholars admit are not correct (see 1 John 5:7, Revelation 22:19). I might conjecture that the reason for omitting footnotes, is to avoid calling into question the long ending of Mark (Mark 16:9-20), which is key to the fundamental teachings of certain Christian persuasions.

That said, I personally think the NKJV is a better alternative to the MEV simply because of the footnotes. But the MEV is a good solid ecumenical translation, aside from that.

Hello and Thank You! Daniel, The thing is I have trouble understanding the

NKJV translation, (maybe because my Bible doesn’t have footnotes?),for

example a passage in Psalms 4:4 (first sentence) says:

“Be angry, and do not sin.

Meditate within your heart on your bed, and be still. Selah.

KJV: “Stand in awe, and sin not.

commune with your own heart upon your bed, and be still. Selah. (Not C.)

MEV:4 Tremble in awe, and do not sin.

Commune with your own heart on your bed, (why commune is capitalized?)

and be still. Selah

Sidenote: Why are their no capitals in the word Sabbath? And other important words? (KJV and MEv)

P.S: The company Thomas Nelson made a comic book for kids, known as BibleForce:The First Heroes Bible. And by the way, what are the words at the end of the sentence of a psalm, for example Selah? Is it a Hebrew word?

Good point, Steve. I have not compared the MEV extensively. I will look into it further. As I point out in my other article, the best Bible translation is the one you read and understand.

Thank you so much for posting that chart, it was exactly what I was looking for today. I enjoyed reading some of your articles this morning and hearing about some of you journey. My uncle has an orthodox study bible which has a footnote regarding the rabbis purging the lxx of references to Messiah. He and I have been looking for more info on this statement, and I wondered if you had come across anything regarding this in your studies. I am adding a link to that footnote, but I don’t know if it will work or not….thank you!

https://books.google.com/books?id=KAh2OOGPsMMC&pg=PA918&lpg=PA918&dq=rabbis+%22purge%22+lxx+of+references+to+messiah&source=bl&ots=bXd37oOjqc&sig=k8GyUQqDm1TCVQ01TUkIvWcPKU8&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiUi6TD1_LeAhVC9IMKHYDnAcYQ6AEwCnoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q=rabbis%20%22purge%22%20lxx%20of%20references%20to%20messiah&f=false

Thank you, Amanda. A very interesting link. No, I hadn’t really researched the differences between the “Christian” Old Testament and the Orthodox Bible. It would be an interesting study. I have only recently begun to use the “Apostolic Bible Polyglot” in my studies, and I’ve found it to be an excellent study tool, to help link some of the linguistic expressions from the Greek NT to their OT roots in the LXX.

Good day!

I read/study from KJV, but on difficult passages, I like to find an easier to read version to help me get a likely understanding of the passage, then return again to that passage in KJV for study.

To me, this is akin to using a bible commentary, getting someone else’s point of view, but it helps me when I go back to KJV, to bring clarity to the passage.

Do you have a recommendation on an easier read version for this review. The CEB has been helpful. But there may be a version unknown to me that has better history.

Thank you!

The chart could be a little fairer if you could subtract for items or issues such as the induced errors of Beza’s and Eramus’s New Testament emendations or the print error in the Textus Receptus at Rev 1:8 that affects all Bible translations using the TR as the translation basis. Maybe John 4:26, is the “I am” together or the I and AM separated in the verse? (It is together in the Greek, Vetus Latina and Peshitta) just some things to chew on.

Maranatha

Thank you, Charles! You have some good points. I think my whole chart is due for an update soon — I’ll try to work on that and I may include comparisons for these texts as well. Blessings to you as you study!

~Pastor Daniel